Competti

Competti

Written by Billy Hani

Illustrated by Precious Narotso

10 min read

“When I started developing feelings of attraction towards women, it was earth shattering. I battle feelings of shame and inner turmoil because there’s what the society expects of me, versus who I actually am,” writes Anne*.

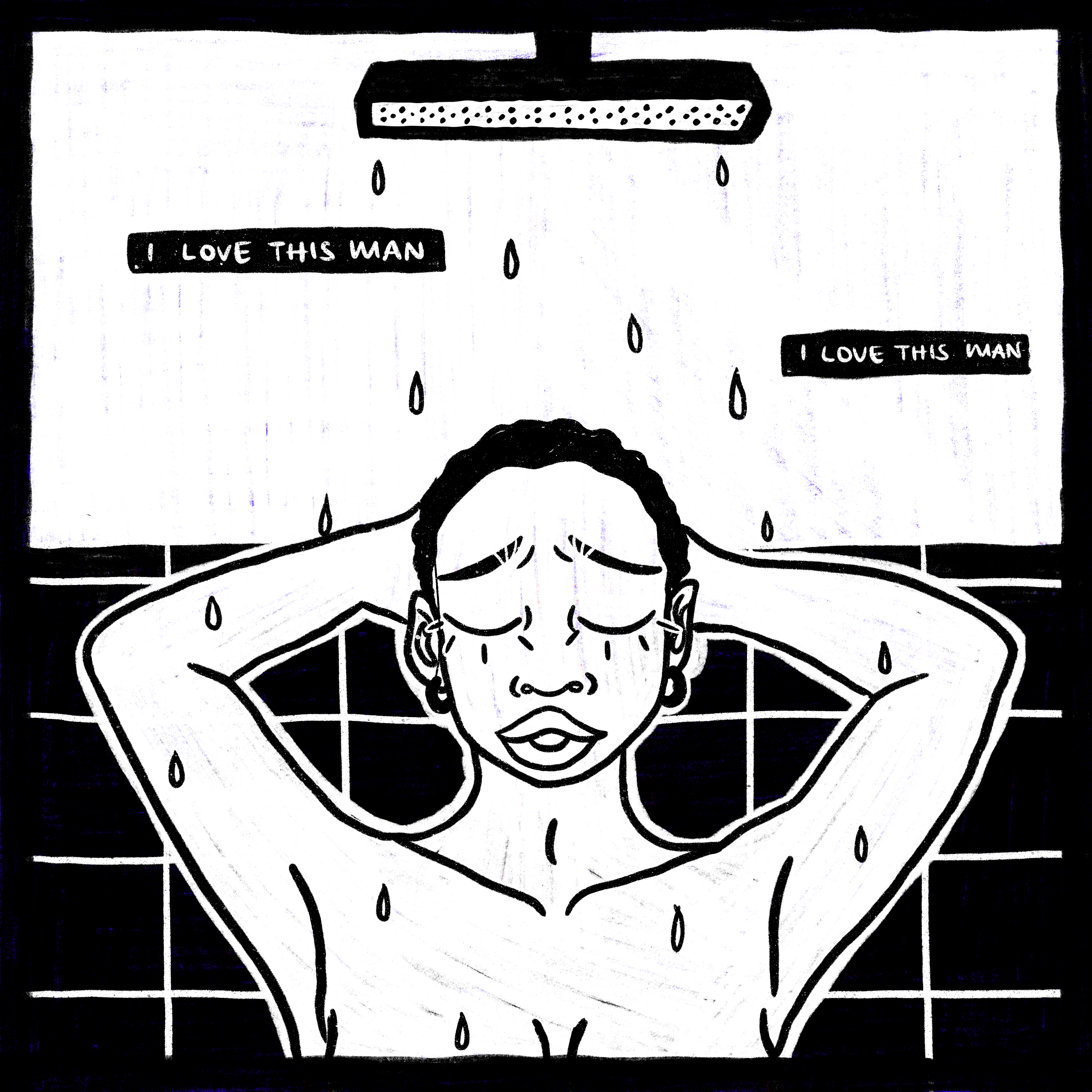

Terry*, a nonbinary lesbian, found themselves constantly convincing themselves that they loved the man they were dating. ‘I would be in the shower telling myself ‘I love this man’constantly even though I didn’t,” they say.

Terry*, a nonbinary lesbian, found themselves constantly convincing themselves that they loved the man they were dating. ‘I would be in the shower telling myself ‘I love this man’constantly even though I didn’t,” they say.

Why would a beautiful thing such as attraction invoke feelings of shame? Why does having a same-sex crush awaken such a turmoil in Kenyans minds? See, in Kenya (and most African countries) if you are born male, the expectation is that you are a boy, you will develop into a

man and finally marry a woman. The same case applies for female children who are expected to grow up as girls, become women and marry men. The phenomenon in the above scenario

is referred to as compulsory heterosexuality, or comphet.

In most African societies, comphet is strictly enforced and children who attempt to deviate

from it are sometimes punished. Interestingly, for a lot of LGBTIQ+ people, the realization

that they were not heterosexual began at a young age. Mario, a 37-year-old gay man says, “I

realized I was different as a child. I used to love playing with dolls and I had a favourite one

called Nelly. Nelly was my great companion and my family did not mind that I was a boy

who had a doll. I used to enjoy dressing it up, and soon I started dressing up myself when

alone. I would use the curtain sheers to create a flowy dress and walk down the room

imitating a wedding, with me as the bride.”

The society has norms and beliefs expected of different genders, often just limited to the

binary genders of man and woman. Men should be ‘manly’ in their mannerisms and dressing.

They should not dress in feminine kind of clothing or be attracted sexually to other men.

Andrew is a gender-non-conforming 25-year-old Kenyan and they have had to shatter these

norms to be able to exist in a society that demands of them to be otherwise. “I realized that I had been practicing compulsory heterosexuality at 19 when I came out to myself. Despite

knowing that I was attracted to boys, I would flirt with girls that I was not interested in, to

seem normal. There was also an expectation on me to be ‘manly’ in terms of the chores I did

around the house. I remember this particular time when my mother called my father asking

him to do something and he retorted that ‘there were boys in the house that could fix

whatever needed to be fixed’ and that he was not the ‘only’ man in the house. As a gender

non-conforming person, I lean more towards feminine presentation and I never really cared to

be ‘manly’.”

While the enforcement of these strict gender norms seems African, most of them are actually

products of colonization. Before colonization, there were no anti-LGBTIQ+ laws in most

African societies. In some cultures, people were more fluid and those who embraced both

their masculine and feminine attributes were revered and considered healers in the society.

There were African women who were Kings like Nzinga of the modern-day Angola. Nzinga

dressed in what would be considered ‘male’ attire and her servants were mostly men who

dressed in more feminine ways. Some African languages such as Kiswahili do not have

gendered pronouns, which is something that gender non-conforming African people have to

grapple with when using languages such as English and French. Faith* embraced her bisexuality after joining the university and meeting likeminded people

who would openly talk about sexuality. Despite having doubts about her sexuality while

younger, she did not have the space and people to talk about it with. She believes that if she

had learnt about sexuality earlier, she would have been more outspoken and probably

impacted on how her family and friends perceive people with different sexualities or genders.

She says, “if I had not been expected to be and to act as a heterosexual woman, even my

artistic expression would have been different.”

Comphet has negative effects on LGBTIQ+ Africans. For Mario, comphet took a toll on his

confidence. “I believe that I could have grown up more confident as a person if I did not have

to perform compulsory heterosexuality. Instead, I grappled with feelings of being abnormal,

guilt and not seeing others who are like me. For a long time, I thought there was something

wrong with me. Had there been not that expectation for me to be a manly heterosexual man, I

would have explored things that I love, free of guilt and embraced myself as I am,” said

Mario. Andrew believes that had it not been for comphet, their academic performance in

school would have been better since they would have focused their energy on other things

like growth and school, as opposed to struggling to pretend to be a heterosexual man.

Comphet also creates a heteronormative culture among LGBTIQ+ people, which consciously

might end up mimicking heterosexual partnerships. For instance, the expectation that one

should have known that they were different from childhood. The assumption of ‘having

known’ fails to take into context the lack of comprehensive sexuality education and spaces

for people to explore. It makes people who come out later in life to feel like they are not

queer enough- further affecting their wellness and quality of life. Truth is, there are queer

Kenyans; young and old, married and married, employed and unemployed.

References:

- Rich, A. (1980) ‘Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence’ Signs: Journal of Women, Culture and Society 5(4): 631-60

- Robinson, B.A. (2016). Heteronormativity and Homonormativity. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies (eds A. Wong, M. Wickramasinghe, r. hoogland and N.A. Naples